TRANSLATING SCIENCE INTO PRACTICE: FMCNA IS AN ECOSYSTEM THAT DRIVES PROGRESS

Fresenius Medical Care North America (FMCNA) is in the ideal position to drive innovation and compress the time it takes to translate science into patient care standards. Our vertically integrated structure encourages us to widen our lens and look at all the clinical, behavioral, and environmental factors impacting our patients’ lives. This unique ecosystem, coupled with FMCNA’s foundational science and engineering DNA, will continue to be a competitive advantage as we embrace a system of value-based care. It empowers us to see new science as it evolves, to focus on how this science can benefit our patients, and to seize the opportunity to reimagine the future of kidney care.

The opportunities for coupling purposeful science with imagination are unlimited. In fact, it’s this sense of infinite possibility that has always given me greater aspirations than the credo of our profession, “First, do no harm.” The need of people with difficult and life-threatening diseases to live full, productive lives challenges us to do more.

For FMCNA, this means broadening our lens to focus on all the elements of both clinical care and daily life that have the greatest potential to improve the lives of people with advanced kidney disease. This demands a multidimensional caregiver focus that considers each individual patient’s unique situation. That broader, fuller understanding is central to our mission of improving the lives of every patient every day.

Seeing that big picture requires expanding our field of vision beyond the lifesaving dialysis therapy to include the full environment in which a newly diagnosed kidney disease patient has an opportunity to understand their disorder while making wise decisions with their caregivers and families. Our goal should always be to help patients live fulsome lives of value—on their terms. This evolution is transformational for FMCNA and represents an approach that will change the landscape of what it really means to be “patient-centered.”

Four key areas will support this evolutionary transformation and change the way we think and act in providing health care. It will set the bar for our ability to harness insights from our broader perspective to organize support for outcome—improving patient care elements from outside the traditional medical-pathophysiological clinical enterprise. These four areas include:

- Speed the translation of scientific advancement into daily practice

- Advocate to reclassify kidney diseases to support more precise medical therapies

- Evolve the elements and processes of care for personalized kidney care

- Recognize the impact of social determinants in kidney disease care

Translating Scientific Advancements Into Daily Practice

The process of scientific breakthrough is fraught with unknowns and challenges, especially in taking fresh knowledge and translating it into the framework of daily practice. FMCNA’s ability to turn novel medical science into routine care is a deep competitive advantage that makes us stand out among health providers. Our vertical integration allows us to see new science as it evolves, consider how it fits into the paradigm for kidney disease care, and launch a process that integrates a valuable new therapeutic advancement into our practicing medical staff’s daily clinical activity (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 | Fresenius Medical Care North America integration

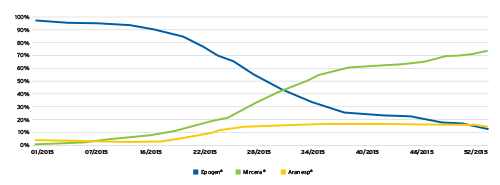

For example, the opportunity to integrate Mircera® (a long-acting erythropoiesis-stimulating agent) into our company’s Fresenius Kidney Care community enabled prescribing physicians to deliver high-value, organized care through an alternative approach and to document the degree to which they adopted these methods for managing kidney disease-related anemia. The 2015 project reduced clinical staff burden, resulting in a more consistent dosing pattern that produced enhanced clinical results (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2 | Fresenius Kidney Care Mircera introduction during 2015

A second example was introducing a tiered approach to thrice-weekly oral calcitriol for the treatment of secondary hyperparathyroidism: First consider the minimal burden therapy; then, if either failure or dissatisfaction by prescribers in primary use clinical results follows, move to more complex or costly therapies. In each case, FMCNA facilitated physicians being able to adopt a desired therapeutic advancement expeditiously. These efforts require access to clinical data that exposes the results, facts, and circumstances present to further discover best practices as they are uncovered within the scientific community.

Reclassifying Kidney Disease to Support More Precise Therapies

With 10 percent of the world’s population affected by chronic kidney disease (CKD), and millions more unaware they have the disorder, the amount of kidney disease-focused clinical research is less than what should be expected for a disease that has been long recognized as a public health condition.1 The funding of clinical trials by the National Institutes of Health for renal-related issues is lower than almost all other major medical specialties.2 One of the fundamental issues may be that our diagnoses and treatments are not as precise and targeted as other specialties, such as oncology. Why is this?

Kidney diseases are classified based on a pathologic classification of disease with minimal opportunity to subclass a disorder by molecular or genetic signatures. Many research facilities have begun to untangle the morass of molecular variations of clinical kidney disorders currently stratified into major classifications such as “Minimal Change Disease,” “Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis,” and “Diabetic Nephropathy.” At the end of the day, all renal disease relates to the loss of either glomerular function or a tubulointerstitial insult that results in destruction of tissue and scarring of the kidney.

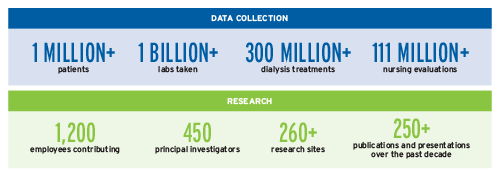

If we can imagine a time when kidney diseases have their pathologic classification enhanced by molecular markers and genetic variations, we can likewise imagine the opportunity to define clear pathways for clinical trials of targeted therapies for the subtypes of today’s classified disorders. This very real opportunity requires a paradigm shift: Instead of having minimal access to research protocols, kidney disease patients would have a robust pipeline of innovative therapeutic alternatives and would always be aware of any trials referencing their specific condition (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3 | Data collection and research

Evolve the Elements and Processes of Care for Personalized Kidney Care

Evolving toward personalized kidney care requires fundamentally reimagining how we listen to patients. This wider perspective requires a much more holistic, “surround sound” approach where we listen to what our patients tell us, what our patient care diagnostics tell us, and, increasingly, what we can learn from the devices and tools that provide their lifesaving dialysis care.

We are thinking more broadly about how the very tools behind our dialysis care can provide an opportunity to collect additional information relevant to both the patients’ treatment and their therapeutic response. By imagining a future where we integrate more advanced sensing into our clinical tools, we can see the possibility of transforming real-time clinical data into actionable information. If we had today’s critical lab tests that gave today’s picture to the clinical team, then we would be able to identify better algorithms to recommend prescription of more precise treatments to address the patient’s present physiologic state, not based on data from potentially weeks ago.

Further, our clinical care devices and machines can collect key information about the patient’s health status during treatment. Cardiovascular health, volume assessment, and heart rhythm become obvious targets of attention when thinking of how dialysis machine diagnostics might influence the patterns of prescribing and care that an individual patient needs.

Providing a more personalized treatment would also dovetail into the opportunity to collect data from the patient’s home environment, and the ability to use the “internet of things” and artificially intelligent systems to package and analyze the impact of that environment.

Recognize the Impact of Social Determinants in Kidney Disease Care

For many of our patients, the toll of chronic illness on their life and the impact their home environment has on their care experience are substantial. These environmental impacts—often referred to as “social determinants of health care”—greatly influence a patient’s ultimate care outcome and utilization of available health resources to address their medical problems.

In the care of kidney disease patients, we have identified five key determinants that will impact their health outcomes and influence the care they need. These five themes are each connected to a clinical result and influence how well patients can succeed in life while living with their kidney disease (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4 | Impact of social determinants

These social determinant themes include:

- Food Security – It’s critical for patients, as well as their caregivers, to have stable access to food in order to maintain good nutrition. Nutrition is the single persistent, independent variable for patients’ survival, and nutritional competence is highly correlated with the ability of patients to survive the rigors of renal replacement therapy.

- Stable Housing – Housing plays a surprisingly important role in the decisions patients make about accessing the health system wisely. Research discovered housing can influence decisions that impact patient outcomes. High hospitalization rates and increased use of emergency departments were highly correlated with housing security issues and were resolved when stable housing environments exist.

- Community – Kidney disease patients benefit from having people to rely on during days when the disease keeps them from being independent. Community can take many forms. It can be family, a nonprofit organization, a faith-based community, a peer-community, or a group of people with a mutual understanding of something they have in common. Many kidney disease patients find that the realization they are not alone can be a great source of strength.

- Kinetics – Patients with advanced kidney disease need to stay moving and active. Kinetic activity supports muscle growth, ambulation, and independence—all crucial for patients who need more than a passive understanding of what their life is like.

- Intellectual Purpose – Motivation and drive to succeed with a life-threatening illness are valuable traits that can help a patient succeed. They’re intrinsic to some patients, but others are heavily influenced by their environment and the goals they have in actively treating their disease. Making sense of the life changes that kidney disease brings—while still living with a sense of intellectual purpose and meaning—plays a key role in their happiness. Recognizing emotions that are common to others with CKD can help patients feel less isolated and take control of their mental state. Even with regular routine care, kidney disease and dialysis come with emotional dimensions. Patients who are highly engaged and motivated tend to participate more in their own care, ultimately leading to improved health outcomes.

While these features of care are not directly part of the pathophysiology of kidney disease itself, these factors do, in fact, have a profound impact on our patients’ outcomes, as well as the perception of their own purpose toward leading lives with meaning and success. Understanding what role FMCNA can play in these arenas is critical to the evolution of our company.

Maria Montessori, the remarkable physician and educator, said, “Imagination does not become great until human beings, given the courage and the strength, use it to create.” At FMCNA we are leveraging our entire ecosystem to reimagine the future of kidney care. The articles in this report reflect the depth of our expertise, the breadth of our current explorations, and the strength of our commitment to continual learning.

Meet Our Expert

Franklin Maddux, MD, FACP

Global Chief Medical Officer, Fresenius Medical Care

Prior to joining FMCNA in 2009, Frank Maddux developed one of the first laboratory electronic data interchange programs for the U.S. dialysis industry. He later created one of the first web-based electronic health record solutions, now marketed under Acumen Physician Solutions. He previously served as chief medical officer and senior vice president for Specialty Care Services Group and is the former president of Virginia’s Danville Urologic Clinic, where he was a practicing nephrologist for nearly two decades. An alumnus of Vanderbilt University, he earned his doctor of medicine from the School of Medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he holds a faculty appointment as clinical associate professor. His writings have appeared in leading medical journals, and his pioneering health care information technology innovations are part of the permanent collection of the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution.

References

Translating Science into Practice: FMCNA is an ecosystem that drives progress

by Franklin W. Maddux, MD FACP

- Schoolwerth, A., Engelgau, M., Hostetter, T., Rufo, K., Chianchiano, D., McClellan, W., Warnock, D., Vinicor, F. Chronic kidney disease: a public health problem that needs a public health action plan. Prev Chronic Dis, April 15, 2006.

- Mendu, M., Erickson, K., et al. Federal funding for kidney disease: a missed opportunity. AJPH, March 2016, Vol 106, No. 3.

- Hardin L, Kilian A, Olgren M. Perspectives on root causes of high utilization that extend beyond the patient. Population Health Management 2017;20(6): 421–24.